‘There’s a Reason I’m Here.’ How One Woman Survived Gunshot Trauma and Its Aftermath

By Mary Frances Emmons, Editorial Contributor

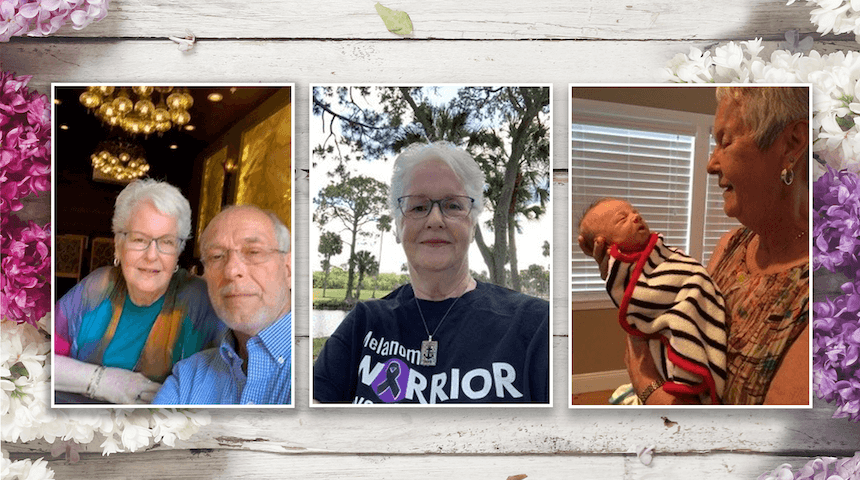

Life was good for Karen Keene and Steve Glassman, the love of her life.

Busy with careers, volunteer work, family and friends, the couple had lived in Maitland for more than 20 years. Football, fishing and travel filled their free time.

It was a breezy spring day on March 8, 2020. Karen and Steve took pictures of their dog, Bella, bounding through flower beds that had just been planted. Later, Steve went into his office to work for a few hours, and Karen headed to the mall. She needed a dress for an upcoming charity luncheon.

“It was quite honestly a typical Sunday,” says Keene, 55. Yet what was about to unfold was not typical in any way.

‘I Thought I Was Going to Die’

By 11 that night Steve was watching TV. Karen was in bed on the other side of the house when she heard a loud noise. In darkness, she crept toward the front of the house for a look, when “all of a sudden the door blew in,” she says. “I couldn’t see who it was — I was terrified.”

She ran back to the bedroom, locked the door and called 911. As bullets started piercing the bedroom door, she fled to the bathroom, still on the phone. The bullets kept coming.

“I wasn’t even listening to the dispatcher. I thought I was going to die.” She lay on the floor, clutching her side, bullet holes and broken glass everywhere. There were pieces of flesh on the wall — her flesh.

Within minutes, someone was banging on the bathroom door — a Maitland police officer. Keene had never seen her attacker’s face.

A World Turned Upside Down

When she came to at Orlando Health Orlando Regional Medical Center a week later, Keene learned the unthinkable. Steve was dead. The shooter was her estranged brother, Kevin, who had killed himself the next day in a standoff with police. Although he had exhibited erratic behavior and symptoms of mental illness for years, “none of us could have imagined he would do what he did,” she says. Her precious Bella, a Shiba Inu-bulldog mix, had been spared.

While Keene was unconscious, COVID had turned the world upside down. Orlando Health ORMC was on lockdown. “I didn’t even know what that meant,” she says. Family who rushed to town could visit only on their first day — after that, her brother Christopher would be her sole connection to the outside world.

Her doctors had been busy. Keene required immediate surgeries, one to place a rod in her right femur so she would not lose the leg. The worse problem was her abdomen.

“She basically had what we call evisceration,” says Dr. Michael Cheatham, chief surgical officer at ORMC. “A shotgun blast had torn a hole in her abdominal wall to where her intestine was protruding from her abdomen.”

Emergency surgery saved Keene’s life. But that was only the beginning.

“The work he has done is nothing short of a miracle,” Keene says of the nearly two dozen surgeries Dr. Cheatham has performed on her. She had also lost a considerable amount of her colon, with damage to her small intestine.

While her brother Christopher was her rock, Orlando Health was her refuge. “For a long time, it was the only place I felt safe,” she says. Slowly she began to realize that everyone around her was coping with their own pandemic-driven fears.

“I was so impressed by their courage, especially at the risk of their own families,” Keene says. “What they do is truly a calling.”

Finding Hope in the Darkness

Gun shots are all too familiar to Dr. Cheatham, who led Orlando Health’s response to the Pulse shootings in 2016. “Being a Level One Trauma Center, we see these types of injuries daily,” he says.

But a shotgun is different. “A handgun is one thing — there’s one projectile,” he says. “A shotgun blast is multiple projectiles — each pellet becomes a new wound. They are very closely patterned, causing severe tissue damage.”

All of a sudden the door blew in. I couldn’t see who it was — I was terrified. I thought I was going to die. – Karen Keene

Keene initially was hospitalized for three months and has had more surgeries since then. In about a year, when her wounds have healed, she will undergo total abdominal reconstruction.

“Shotgun blasts are devastating — you frequently have to deal with the aftermath for months to years later,” Dr. Cheatham says.

For Keene, that has included a temporary colostomy; fistulas that caused stool to drain through the abdominal wall; cardiac arrest triggered by electrolytes leaking out through the bowel; and wounds that are still draining.

Not all patients can take it. “There are people who don’t survive injuries like this,” Dr. Cheatham says. “Not having experience with traumatic injury, patients don’t see any hope. I reassure them there will come a time when the dark days are in the past.”

“It’s amazing we’ve gotten this far and I’m doing as well as I am,” Keene says.

Working for Change

Keene has always had a positive attitude, “and that was a huge help,” Dr. Cheatham says.

Keene, who at the time of the attack was director of marketing and business development at Dean Mead law firm, is no longer working. She’s taking life a little slower these days and appreciating the natural world even more. She moved to Heathrow, to a house that backs up to the Wekiva River basin, where every day is filled with birds, deer and long walks with Bella.

“It’s absolutely the right place,” she says. “I love it here.”

Her journey back started in the hospital. “You’d be surprised by the simple things I had to relearn,” she says, like taking a single step. She was defeated and in excruciating pain. But her physical therapists encouraged her to “feel the fear and keep moving forward anyway.”

Today she works on strength with a personal trainer and hopes to return this year to her passion, developing young emerging women leaders through Athena Orlando Women’s Leadership, a volunteer network she co-founded. She also works on her PTSD with a counselor who connected her to Everytown Survivor Network, a nationwide community working to end gun violence.

“We need to look at reform as it relates to mental illness,” says Keene, who before the shooting had not seen or spoken to her brother in more than a year. “It shouldn’t be so easy to buy guns on the internet,” where her brother amassed “an arsenal.”

It’s a concern shared by Dr. Cheatham, who has lobbied Congress to fund research.

“Ever since Pulse I’ve been dumbfounded that fire-arms research is discouraged,” he says. “There’s extensive literature on trauma by motor-vehicle crashes — that data saves lives.” Evidence shows fatalities drop as funding for research increases.

“I want to see change in our country,” says Keene, who is working on a book about her experience. “There’s a reason I’m here.”